During a couple of summers in college, my housemates and I cooked at home, and I realized how much of our food landed in the trash. As a kid, I almost never saw this happening at home; wasted food meant wasted money and wasted labor, from all the folks who harvested, transported, and prepared the ingredients. Even with this in mind, though, I still mismanaged the food in my own kitchen — and I realized that with about 1/3 of all food lost or wasted worldwide, other folks had similar problems at scale.

When I returned to my senior year, I searched how to address food waste outside my residence. I volunteered at Stanford Food Recovery to redirect surplus food to nearby communities. I helped organize Stanford Food Design Lab‘s FoodInno conference around food waste reduction. Since then, I’ve reduced grocery-wide food waste as an applied scientist and machine learning engineer at Afresh.

As an informal advocate for food waste reduction for the past 7 years, I figured I’d share some personal notes I cite!

Frequently Asked Questions

❓ How much food is lost or wasted anyway?

About 1/3 of all food produced is lost or wasted[1] at some point in the food supply chain worldwide. This translates to roughly 1.43 billion tons and $1 trillion per year (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations i.e. FAO)! For comparison, this amount weighs slightly more than all the mammals on earth combined (source).

In the United States, about the same proportion of food is lost or wasted (30-40%), which translates to roughly 80 million tons of food per year — or about 1.3lbs per person per day!

🍌 What about inedible portions of loss or waste? Are they counted?

According to ReFED’s assessment in the United States: “Of all surplus food, only 22% was inedible parts; an additional 33% was spoiled or discarded due to safety concerns. That means around 45% of surplus was still considered fit for human consumption at the time of disposal.” (Of course, the spoilage is also often preventable by interventions early in the supply chain!)

🌏 What are the implications for the environment?

They’re huge! I discuss how food systems contribute to Earth’s exceeding multiple planetary boundaries in a previous post, but in summary:

- Climate change: about 26% of greenhouse gas emissions (by CO2 equivalents) comes from food production (Our World in Data), or equivalently, about 10% of greenhouse gas emissions comes from food loss and waste (WWF). If food wastage (so both loss and waste) were a country, it would be the third largest emitter of greenhouse gases, behind China and the United States. With this magnitude, food waste reduction is listed as one of Project Drawdown’s most impactful ways to reduce carbon emissions.

Nutrient pollution: about 90% of reactive nitrogen inputs from humans occur through agricultural activities, such as applying synthetic fertilizer. Imbalance in the nitrogen cycle means eutrophication, which means deprives marine life from enough oxygen, loss of soil nutrition, biodiversity loss, and increase in atmospheric nitrogen oxides.

Land use: about 50% of habitable land is used for agriculture, most of which is devoted to livestock (Our World in Data). The land devoted to producing lost or wasted food would be the second largest country in the world by area! (University of California)

🚚 Where is food lost in the supply chain, and why?

The proportions differ depending which part of the world we’re looking at. ReFED breaks down the percentage lost/wasted at each supply chain step. Note that while waste in the home occupies the highest percentage, that waste could’ve been prevented by smarter decision-making earlier in the supply chain. A grocery store with strawberries nearing perishability might advertise a steep discount to clear that inventory, leaving the consumers to throw out any spoiled strawberries.

FAO also provides a summary of ways food might be lost or wasted along the path to the consumer.

🌾 What types of food are wasted the most often?

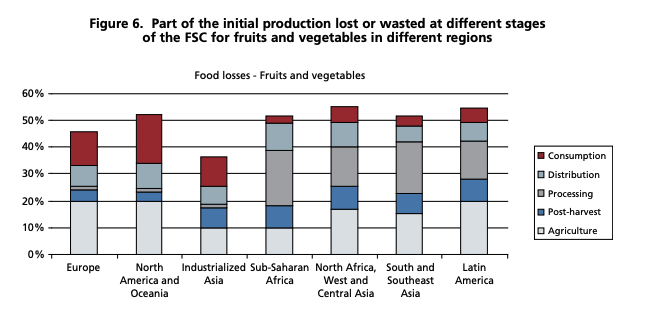

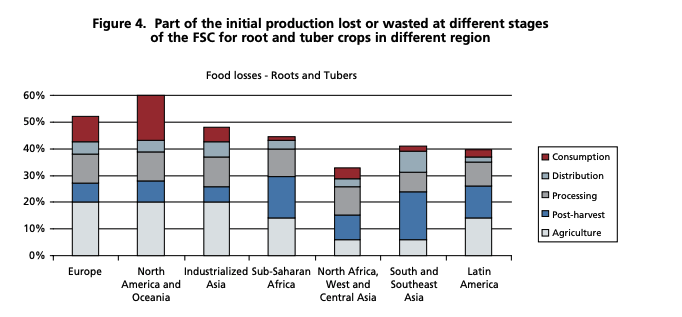

The below charts come from FAO. By weight, we produce the most cereal crops (i.e. grains), followed by fruits + vegetables, so the majority of food wastage comes from cereal crops.

However, by proportion, we lose the most from fruits and vegetables.

💡 What can we do to reduce food loss or waste?

A lot! This is by no means an exhaustive list, but here are some ideas more focused on the United States, especially in California where I currently reside. (Table 3 in this article breaks down a more comprehensive categorization of potential solutions.)

Policy

Date labeling: some labels such as “sell by”, “best if used by”, or “best by” don’t pertain to food safety; they’re guides for when an item might be at peak quality or for how a retailer should handle its inventory. An item might be unsafe to eat before its sell by date, or it might still be high quality after its labeled date (NRDC). There’s also no industry consensus for what these terms actually entail (and state laws vary), leading to retailer and consumer confusion and food waste. It’s estimated that about 7% of US food waste results from no label standardization.

The FDA and USDA are exploring standardizing these labels, and some states have taken steps in that direction as well. California’s AB 660 will prohibit the “sell by” label in 2026.

Organic waste: although ideally food waste is prevented further upstream, we can at least compost it; otherwise, sending that waste to the landfill generates methane gas (a potent greenhouse gas). California’s SB 1383 calls for 75% landfill diversion of organic waste by 2025 (and for at least 20% of currently disposed surplus food to be recovered — discussed more below!)

Supply chain design:

- Optimized planning: retailers or distribution centers might blanket overorder to avoid out-of-stock events, and for fresh items like fruit and vegetables, this overordering leads to food waste. However, better optimized ordering solutions such as Afresh might cut excess ordering while still maintaining sufficient inventory levels (ex. keeping shelves full at the grocery store).

Food recovery / rescue

Nonprofit food rescue: organizations like Replate and Copia redirect surplus food from businesses (who receive tax benefits) to non-profits. This coordination poses a nontrivial matching problem, as every non-profit has different capacity, food type, and time requirements, but food is a perishable good. (When I volunteered with Stanford Food Recovery, we worked with Silicon Valley Food Recovery and Loaves and Fishes, nonprofits that handled both the surplus food pickup and the direct donation to local communities.)

Secondary markets: Too Good to Go allows restaurants or grocery stores to sell surplus “surprise bags” at discounted prices. In the same vein, Flashfood partners with grocery stores and lists deals for food approaching their best-by dates. Misfits Market offers a grocery delivery program for “ugly produce” and other imperfect items.

Upcycling: this means transforming surplus food into innovative products! Renewal Mill converts okara, the pulp from soymilk processing, into a low carb flour. Regrained (now Upcycled Food Lab) converts the spent grain from brewing beer into powder, to add to snack bars or sourdough.

Final Thoughts and Resources

It’s easy to forget about the food we lose or waste once it reaches the garbage bin (or ideally the compost bin). My hope, though, is that the above information convinces us that food loss and waste isn’t an issue we can ignore, and that we have low-hanging fruit to address it.

If you’d like to learn more about the high level issue:

- ReFED provides an overview of loss and waste in the United States, and their Insights Engine features a solutions database and policy finder for in the United States

- Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations discusses the worldwide problem in their reports here and here, including breakdown by food category and geographic region.

A thank you to John McIntosh for providing feedback and to everyone who’s put up with my advocacy over the years!

According to FAO, food waste is “the decrease in the quantity or quality of food resulting from decisions and actions by retailers, food services, and consumers.” Food loss results from decisions and actions earlier in the food supply chain.