“One at a time please!”

My dad translates for my great aunt, who we’re visiting in Asia, to the rest of the family. She’s having trouble understanding the 5-way conversation, and while my lack of fluency in her native language doesn’t help, I know her weaker hearing is the main factor. She does own assistive hearing devices, but she complains that they amplify too much background noise, so today, we just slow the rhythm of conversation.

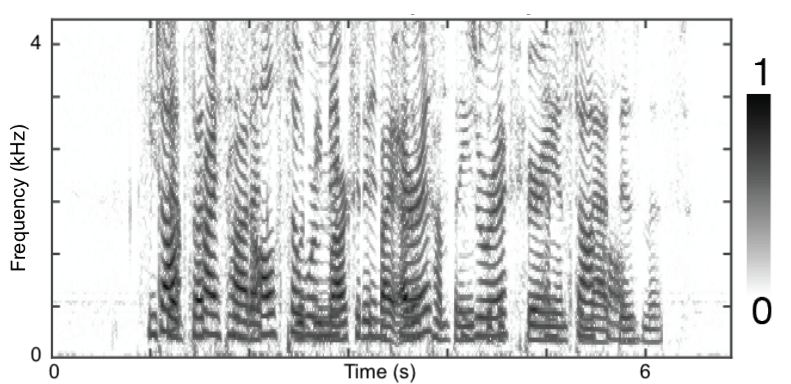

To a smaller extent, I myself also struggle with this issue. Until 2nd grade, I had poor listening comprehension, which meant that discerning and processing multiple voices took extra effort, and even today, I opt for less chaotic audio spaces when possible. I can understand how even with visual cues, it’s difficult to parse crowded soundscapes like this:

In the machine learning (ML) world, this problem of separating voices (perhaps to amplify the important ones) is called the cocktail party problem. The literature is rife with obstacles in audio processing, stable model training, etc, but the story that stands out revolves around lag: how much audio needs to elapse before speech separation can start?[1]

Before we jump into the rabbit-hole exploring this lag, I should preface that:

- We focus on the ML problem and less on how speech separation gets productionized in hearing devices, which I know much less about!

- We aren’t diving into a comprehensive literature review of speech separation; we are focusing on models pre-transformer era, as these older models help us understand fundamental aspects of this problem.

- The remainder of this post assumes a moderate understanding of deep learning. We can skip to the side-by-side comparison section at the end if the technical details aren’t of interest!

Background

In this version of the cocktail party problem, we assume we have $C$ speakers (with $C$ known in advance) talking simultaneously to produce a mixed signal: a single time series of decimal numbers. (In other words, we’re working with mono audio, not stereo audio.) Given this mixed signal, our goal is to separate it back into the individual speakers’ signals. In a hearing device scenario, we then decide how to reconstruct “cleaner” audio that’s helpful for the device user; for example, we could amplify the loudest speakers and mute the remaining speakers.

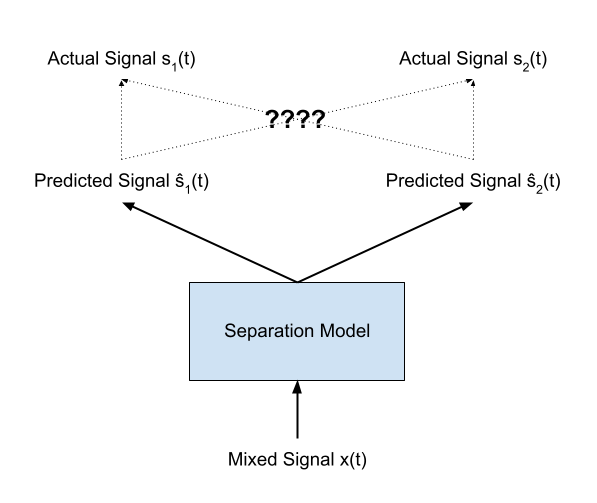

Formally, we have $C$ speaker sources $\mathbf{s}_1(t), \ldots, \mathbf{s}_C(t)$ that sum to the mixture waveform signal $\mathbf{x}(t)$. The goal of speech separation, then, is to derive estimates $\mathbf{\hat{s}}_i(t)$ given just $\mathbf{x}(t)$, ideally so that $\mathbf{\hat{s}}_i(t) \approx \mathbf{s}_i(t)$.

In many audio applications, we work in the frequency domain; at a high level, we’re expressing the original audio signal as a (weighted) combination of waves with various frequencies. The frequency of a wave corresponds to pitch.

Frequency components can change quickly over time, so to convert between the original time domain and the frequency domain, we might apply a short-time Fourier transform (STFT) to frames of time, say 32ms each. We can then represent the audio as a 2D spectrogram.

We say this representation lives in the time-frequency (TF) domain, and we say this spectrogram is a grid of TF bins, each with a magnitude.

Breaking a raw audio signal into its time-frequency components offers a more intuitive structure for the sound; most relevant to us, we can roughly partition the above spectrogram over speakers.

In the context of the speech separation problem, the time-frequency domain representation has a similar setup as the time domain version; we have a mixture signal that’s a sum of source signals. To convert the time-frequency signal back to the time domain signal, we can apply an inverse STFT[2]: $$ \begin{align*} \mathcal{X}(f,t) &:= STFT(\mathbf{x}(t)) \\ \mathcal{X}(f,t) &= \sum_{i=1}^C \mathcal{S}_i(f,t) \\ \mathbf{s}_i(t) &= STFT^{-1}(\mathcal{S}_i(f,t)) \end{align*} $$

Hearing assistive devices often process sound in the time-frequency domain; however, as we’ll see, speech separation algorithms have used both time-frequency domain and time domain representations.

Evaluation

Perhaps the primary benchmark dataset for speech separation is WSJ0-2mix; it combines pairs of ~3-8 second clips of the Wall Street Journal news, representing different gender combinations. In total, the training set consists of 30 hrs of mixed audio. Some papers also use WSJ0-3mix, which is constructed the same way with triples of clips. Note that while these datasets cover a wide range of spoken vocabulary, they are sanitized versions of the audio that one might hear in real life.

Researchers measure speech separation models with scale-invariant signal-to-noise ratio improvement (SI-SNRi). We can break the definition down:

Signal-to-noise ratio (SNR): the log ratio of the true signal against the unwanted signal (with some scaling). If $s$ is the true signal and $\hat{s}$ is the predicted signal (as vectors), then SNR is:

$$ SNR(\mathbf{s}, \hat{\mathbf{s}}) := 10\log_{10}\frac{||\mathbf{s}||^2}{||\mathbf{s} - \hat{\mathbf{s}}||^2} $$

The units are decibels, as they’re also on the log-10 scale!

Scale-invariant SNR (SI-SNR): to make the metric insensitive to amplitude, we can instead look at the orthogonal projection of $\hat{s}$ onto $s$’s line.

$$ SI\text{-}SNR(\mathbf{s}, \hat{\mathbf{s}}) := 10\log_{10}\frac{||\alpha \mathbf{s}||^2}{||\alpha \mathbf{s} - \hat{\mathbf{s}}||^2}\text{ for } \alpha = \frac{\langle \mathbf{s}, \hat{\mathbf{s}} \rangle}{||\mathbf{s}||^2} $$

SI-SNR improvement (SI-SNRi) represents the improvement moving from the mixed signal to the estimated source signal (so higher values are better):

$$ SI\text{-}SNRi(\mathbf{x}, \mathbf{s}, \hat{\mathbf{s}}) = SI\text{-}SNR(\mathbf{s}, \hat{\mathbf{s}}) - SI\text{-}SNR(\mathbf{s}, \mathbf{x}) $$

To better understand what the SI-SNRi values entail, we can listen to a few examples.

| Description | Audio Example | SI-SNRi Value |

|---|---|---|

| The original mixed audio (taken from the dataset) | 0.00 dB | |

| Source 2 decreased by 5 dB[3] | 5.33 dB | |

| Source 2 decreased by 10 dB | 10.25 dB | |

| Source 2 decreased by 15 dB | 15.15 dB | |

| Source 2 decreased by 20 dB | 19.86 dB | |

| Source 2 decreased by 30 dB | 26.93 dB |

We should keep in mind that SI-SNRi is just one metric, and it may not capture overall sound quality. (See this resource for more about speech separation metrics.) However, with at least a better understanding of how we evaluate speech separation architectures, we can start exploring!

Deep Clustering (DPCL)

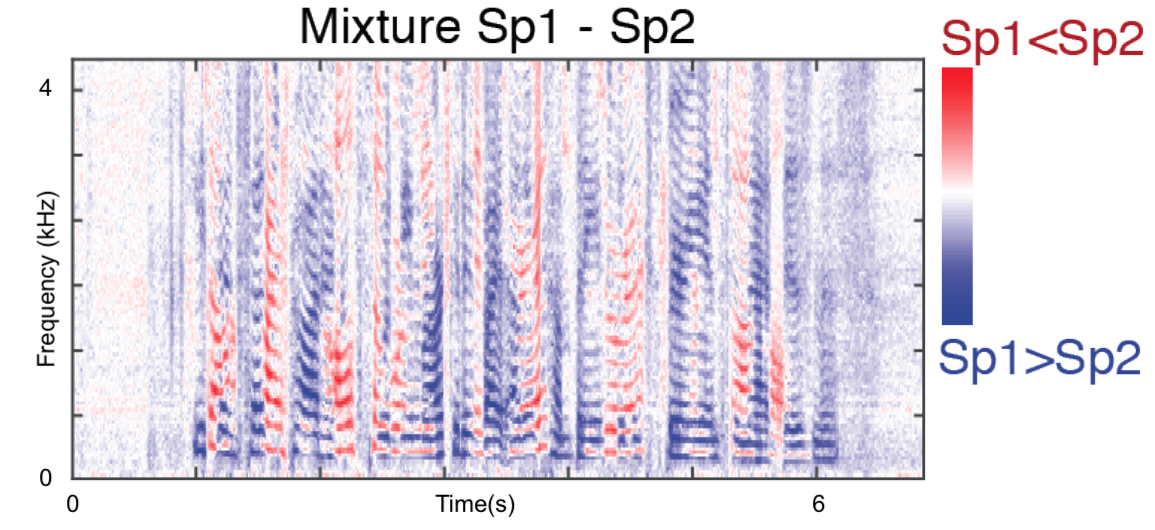

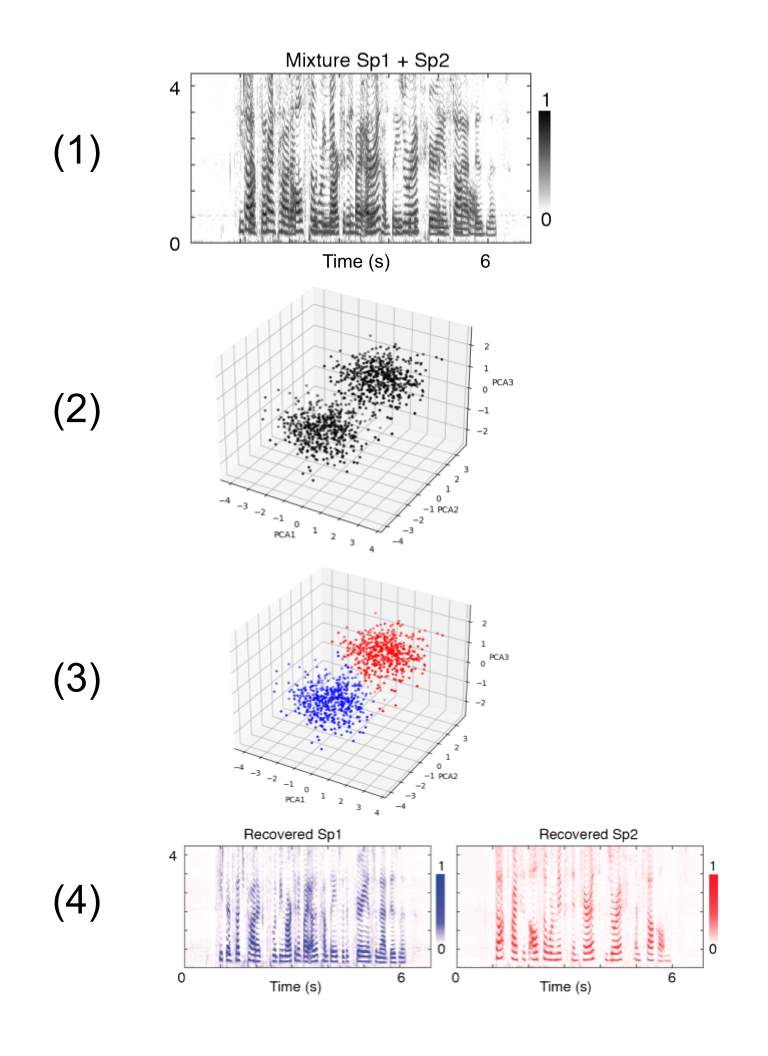

The seminal article establishing the WSJ0-2mix dataset in 2015 also proposes a speech separation architecture called deep clustering (DPCL). The motivation is that we should be able to project the TF bins into a higher dimensional space, so that bins associated with Speaker 1 are clustered together, and bins associated with Speaker 2 are clustered together elsewhere. More precisely, DPCL does the following:

Preprocessing: we start with a speech signal divided into 100-frame windows (where each frame is a 32ms window, spaced 8ms apart), and we compute its representation in time-frequency domain. For a given set of 100 frames $\mathbf{x}_1, \ldots, \mathbf{x}_{100}$, let’s say the resulting TF representation is a set of vectors $\mathcal{X}_1,\ldots, \mathcal{X}_{100}$ each of length $N$ (so $N$ is the number of TF bins).

Embedding: we use BLSTM layers (plus a feed forward layer) to map $\mathcal{X}_1,\ldots, \mathcal{X}_{100} \in \mathbb{R}^N$ to $\mathcal{V}_1,\ldots, \mathcal{V}_{100} \in \mathbb{R}^{N \times K}$. We can then re-express:

$$ \mathbf{V} := \begin{bmatrix}\mathcal{V}_{1} \\ \vdots \\ \mathcal{V}_{100} \end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix}\mathbf{v}_{1} \\ \mathbf{v}_{2} \\ \vdots \\ \mathbf{v}_{100N} \end{bmatrix} $$

so each $\mathbf{v}_{j} \in \mathbb{R}^K$ is the embedding of a TF bin from the $(\lfloor j / N \rfloor + 1)$th frame. Ideally, the points $\mathbf{v}_{j}$ should be well-clustered, so each cluster represents a single speaker!

Clustering: to decide the $C$ clusters in the embedding space, we run k-means clustering.

Reconstructing: for each cluster $i=1,\ldots,C$, we apply a mask onto $\mathbf{V}$ so the entries corresponding to $\mathbf{v}_i$ in cluster $i$ stay as they are and the remaining entries are 0. We map the resulting vector back to $\mathcal{S}_{i,1}, \ldots, \mathcal{S}_{i,100} \in \mathbb{R}^N$ in the original TF space. We can then convert back to time domain to get the final $\mathbf{s}_{i,1}, \ldots, \mathbf{s}_{i, 100}$.

Not any function that maps between $N$- and $K$- dimensional spaces will cluster the speech signal; we train the embedding function to minimize the objective:

$$ \mathcal{L}(\theta) = \sum_{i,j \in {1,\ldots, N}: y_i=y_j} \frac{(\langle \mathbf{v}_{i}, \mathbf{v}_j \rangle - 1)^2}{d_i} + \sum_{i,j\in {1,\ldots, N}: y_i\neq y_j} \frac{(\langle \mathbf{v}_i, \mathbf{v}_j \rangle - 0)^2}{\sqrt{d_i d_j}} $$

where $\mathbf{v}_j$ is an embedded point (mapped from a TF bin), $y_j \in {1,\ldots, C}$ represents which speaker was assigned to $\mathbf{v}_j$, and $d_i := |{j: y_i = y_j}|$. Intuitively, this objective encourages points belonging to the same speaker to map close to each other (with dot product close to 1) and bins belonging to different speakers to map far from each other (with dot product close to 0), adjusting for the frequency of each label. The embedding function (on the TF spectrogram) chosen consists of two BLSTM layers followed by a feed-forward layer.

In this form, the training is not quite end-to-end; it doesn’t involve the clustering step because it is not differentiable and therefore doesn’t produce feasible gradients. That means the model is not actually optimized for speaker separation; for instance, it treats TF bins with low signal (like silence regions) with the same weight as TF bins with high signal. To address this issue, we can follow-up with DPCL++; among other improvements, this sequel replaces the k-means with a “soft k-means”. Instead of assigning each TF bin with a strict assignment to a single speaker, we provide a probability distribution over the possible speakers. During training, we can then train an end-to-end model by backpropagating through the soft k-mean iterations.

This architecture serves as a nice fundamental model because we can easily visualize how the model assigns speaker labels to the TF bins. However, this approach also requires 100 frames at a time because we need enough embedded points to form clusters. However, this translates to ~824ms (32 ms for 1st frame, and then 8 ms for the remaining 99 frames)[4], which means we need to wait for that lag before starting speaker assignment. That makes DPCL and its variants ill-suited for hearing devices, which need real-time computation.

Utterance-Level Permutation Invariant Training (uPIT)

To avoid the aforementioned lag, the next generation of separation models do away with clustering and instead process the audio signal one frame at a time. Given a new frame, we can immediately decompose it into an output signal for speaker 1, an output signal for speaker 2, etc. In training, we have a classic supervised learning problem, where our goal is to minimize the loss between each predicted output signal and each actual speaker signal — simple, right?

Well, almost. In moving away from clustering, we lose one nice property: permutation invariance. Let’s say during training, we decompose a mixed signal $\mathbf{x}(t)$ into two output signals $\hat{\mathbf{s}}_1(t)$ and $\hat{\mathbf{s}}_2(t)$. The training loss could be either $$ \mathcal{L}(\mathbf{s}_1(t), \hat{\mathbf{s}}_1(t)) + \mathcal{L}(\mathbf{s}_2(t), \hat{\mathbf{s}}_2(t)) $$

or

$$

\mathcal{L}(\mathbf{s}_1(t), \hat{\mathbf{s}}_2(t)) + \mathcal{L}(\mathbf{s}_2(t), \hat{\mathbf{s}}_1(t))

$$

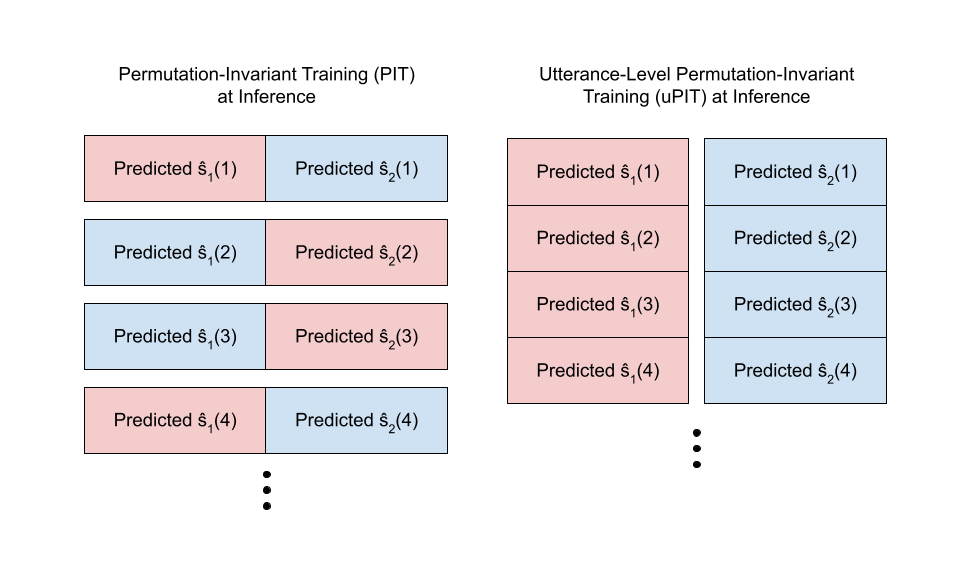

One natural approach taken in permutation invariant training (PIT) is for each frame, we independently pick the permutation with the lowest loss. That there’s always a well-defined computation for the loss and thus how to backpropagate during training. In the two-speaker setting, the loss for a given frame is: $$ \min\left(\mathcal{L}(\mathbf{s}_1(t), \hat{\mathbf{s}}_1(t)) + \mathcal{L}(\mathbf{s}_2(t), \hat{\mathbf{s}}_2(t)), \mathcal{L}(\mathbf{s}_1(t),\text{ } \hat{\mathbf{s}}_2(t)) + \mathcal{L}(\mathbf{s}_2(t), \hat{\mathbf{s}}_1(t))\right) $$ That means in the first frame, we might match $\hat{\mathbf{s}}_1(1)$ with $\mathbf{s}_1(1)$, whereas in the second frame, we might instead match $\hat{\mathbf{s}}_2(2)$ to $\mathbf{s}_1(2)$ if that’s what minimizes the loss. That’s okay for training, but now what about at inference time? There’s no known loss to minimize anymore, so the permutation might still “flicker” between frames.

Instead of computing the loss for each frame independently and aggregating across frames, what if we compute the loss per utterance (batch of a few seconds’ worth of frames)? Formally, if $S_C$ represents the set of permutations of the $C$ speakers, this means instead of computing: $$ \sum_{t} \min_{\sigma \in S_c} (\mathcal{L}(\mathbf{s}_1(t), \hat{\mathbf{s}}_{\sigma(1)}(t)) + \mathcal{L}(\mathbf{s}_2(t), \hat{\mathbf{s}}_{\sigma(2)}(t))) $$

we instead compute:

$$ \min_{\sigma \in S_c} \sum_{t} (\mathcal{L}(\mathbf{s}_1(t), \hat{\mathbf{s}}_{\sigma(1)}(t)) + \mathcal{L}(\mathbf{s}_2(t), \hat{\mathbf{s}}_{\sigma(2)}(t))) $$ That means that we assume the permutation is consistent for all the frames within an utterance.

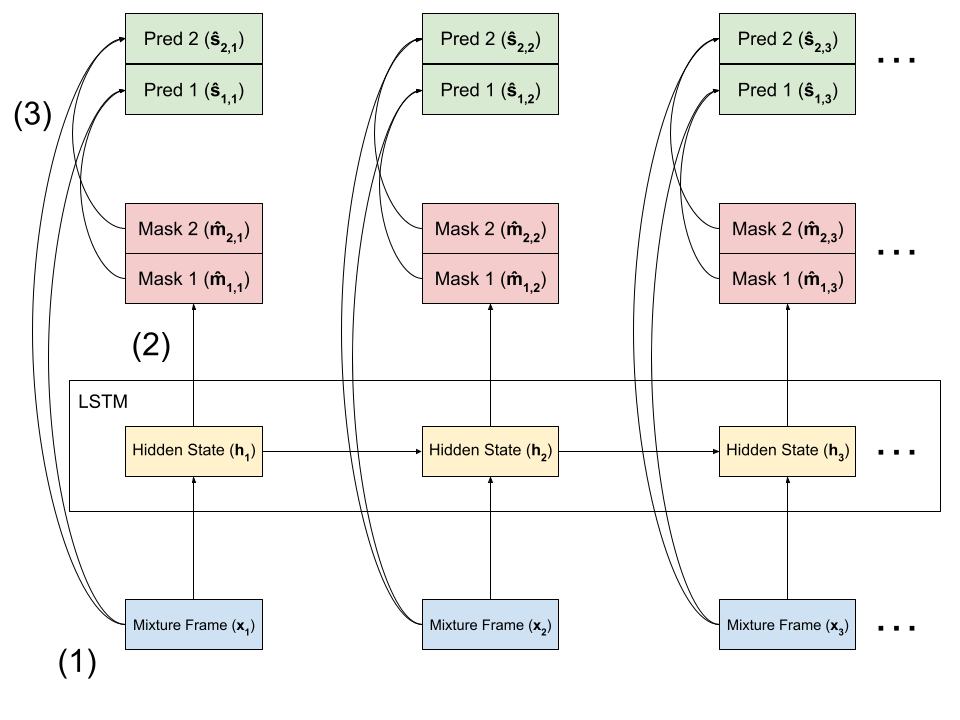

The resulting utterance-level permutation invariant training (uPIT) algorithm still maintains a simple inference process:

- Preprocessing: we start with a speech signal separated into 32ms frames, spaced 8ms apart. We convert each frame into the time-frequency domain. Let’s say that an utterance consists of frames $\mathbf{x}_1, \ldots, \mathbf{x}_M \in \mathbb{R}^N$.

- Mask Computing: we feed the frames $\mathbf{x}_j$ through a deep LSTM, which outputs a set of masks $\mathbf{\hat{m}}_{i, j} \in [0, 1]^{N}$ for speakers $i = 1,\ldots,C$. Each mask indicates how to segment out a given speaker. Note that in this classical RNN architecture, each frame is computed one at a time, and the $j$th hidden state used to compute the $\mathbf{\hat{m}}_{i, j}$ uses information from $\mathbf{x}_1, \ldots, \mathbf{x}_{j-1}$.

- Masking: we then recover our estimated speaker signal by applying the masks to the original mixed frame: $$ \mathbf{\hat{s}}_{i,j} = \mathbf{\hat{m}}_{i,j} \circ \mathbf{x}_j $$

Because of the uPIT training process, we expect that $\mathbf{\hat{m}}_{1, j}$ corresponds to the same speaker for all frames $j$, and similarly for $\mathbf{\hat{m}}_{2, j}$.

This setup allows us to process audio signal without as much lag as DPCL(++), which represents a major step towards real-time processing. However, the next generation of speech separation models take another step by changing the preprocessing step.

Time-Domain Audio Separation Network (TasNet)

If we skim the Papers with Code leaderboard for the WSJ0 2-mix dataset, we might notice that the majority of models opt for a time-domain representation, not a TF-domain representation! This discovery is intriguing, as many hearing aids still favor the TF domain, and speech recognition models such as Whisper do use TF spectrograms — so there must be a good reason to move away! As we’ll see in this section, latency becomes one major consideration.

One of the early architectures in this line of time-domain models is TasNet (time-domain audio separation network). In this setup, we represent the speech signal as a linear combination of “basis” signals[5]. More formally, we can express any input signal $\mathbf{x}$ (in the time domain, this is just a real-valued vector of length $L$) as a nonnegative weighted sum of basis vectors $\mathbf{B} = [\mathbf{b}_1 \cdots \mathbf{b}_N] \in \mathbb{R}^{N\times L}$, where $N \approx 500$ and $L \approx 40$:

$$ \begin{align*} \mathbf{x} &= \mathbf{wB} \\ \mathbf{w} &\in \left(\mathbb{R}^+\right)^{1 \times N} \end{align*} $$

This representation means that even without the clean segmentation offered by the TF domain, there’s still a meaningfully way to separate the mixture by masking $\mathbf{w}$.

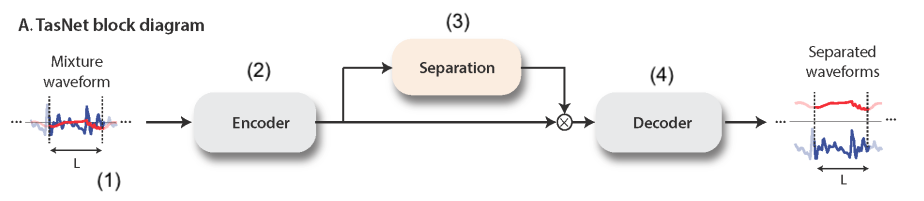

The TasNet architecture follows an encoder-decoder architecture:

- Preprocessing: segment the mixture signal into $K$ windows $\mathbf{x}_k$, each of length $L \approx 40$ frames. (That is, we’re assuming the mixture signal has length $KL$.) This step can also run in a streaming fashion.

- Encoding: compute the nonnegative weights $\mathbf{w}_k$ that represent $\mathbf{x}_k$ in the basis space. We can express these weights as a matrix $\mathbf{W} \in \mathbb{R}^{K \times N}$. The encoder uses a 1D gated convolutional layer.

- Separating: compute the masks $\mathbf{M}_c \in \mathbb{R}^{K \times N}$ for each speaker source $c = 1,\ldots, C$ for each segment. Each mask has entries between 0 and 1. We use a deep LSTM network for this step, so we infer on the $K$ frames in sequence.

- Decoding: apply each mask to the basis weights, and then reconstruct the speaker signal using these masked weights. More precisely, if $\mathbf{B} \in \mathbb{R}^{N \times L}$ represents the basis signals: $$ \begin{align*} \mathbf{D}_c &= \mathbf{W} \odot \mathbf{M}_{c} \\ \mathbf{S}_{c} &= \mathbf{D_cB} \end{align*} $$

We can train the full end-to-end pipeline, learning the basis signals $\mathbf{B}$ jointly with the encoder and separator’s parameters, and optimize for the SI-SNRi directly.

We spot a couple of striking advantages of TasNet over prior methods:

- Unlike DPCL, TasNet is designed to run in real-time, which is necessary for hearing aid purposes. (In the literature, TasNet is called a causal method.) Windows are processed independently from each other except in the encoder, which only introduces dependencies on previous windows. In DPCL, we needed to process in 100-frame batches, which puts us behind real-time.

- TasNet’s latency is significantly lower than previous TF methods, such as uPIT. In TasNet, each window is only ~40 frames at 8 kHz. Processing each window requires no dependency on future windows, so with fast enough inference, the latency is just over 5ms. In contrast, TF processing already requires 32ms windows, so even with an algorithm with only forward dependencies, any TF method would require more latency.

A follow-up model, called Conv-TasNet, replaces the encoder’s LSTM with a temporal convolutional network (TCN), which shrinks the model size by >6x, increases the inference speed by >10x, and maintains similar performance. Most follow-up models now use TasNet-LSTM and/or Conv-TasNet as their performance baseline.

Side-by-Side Comparison

We can roughly summarize our adventures — moving from clustering and TF methods to streaming and time-domain methods — in the following table. The exact numbers might vary depending on the implementation, but the Conv-TasNet paper features all of these models in its results. (Unfortunately, uPIT does not have any public results with the SI-SNRi metric, so we instead add results with signal-to-distortion ratio improvement [SDRi].)

| Algorithm Required | Time Lag (i.e. size of window) | Domain | Model Performance (SI-SNRi on WSJ0-2mix) | Model Performance (SDRi on WSJ0-2mix) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DPCL++ (2016) | 824 ms (32 ms for 1st frame, and then 8 ms for the remaining 99 frames)4 | Time-Frequency | 10.8 | 10.8 |

| uPIT-LSTM (2017) | 32 ms (for applying STFT) | Time-Frequency | - | 7.0 |

| TasNet-LSTM (2017) | 5 ms | Time | 10.8 | 11.2 |

| Conv-TasNet (2018) | 2 ms | Time | 10.6 | 11.0 |

The required time lag serves as a lower bound for the overall latency; the actual latency needs to account for computation time, which depends on the hardware. On a CPU, TasNet-LSTM might require about 860 ms to separate one second of audio while Conv-TasNet would require about 100 ms. A GPU can speed that computation by 10x.

Note that DPCL requires 100 frames (because they require clusters), which means that its required time lag disqualifies it from real-time applications. We can see that these algorithms’ performances are on par with each other; however, the TasNet algorithms have much lower required lag. The uPIT and TasNet algorithms also have bidirectional LSTM versions (which are thus not applicable for real-time), but significantly outperform DPCL models.

Of course, since 2018, we’ve seem significant progress in model performance; recall that a score around 10-11 dB SI-SNRi leaves much room for improvement. We can see on the Papers with Code leaderboards for WSJ0-2mix and WSJ0-3mix that transformer-based models such as MossTransformer2 and SepTDA top the lists with >20 dB improvements. (The metric used — SI-SDRi — is identical to SI-SNRi[6].) Among these new time-domain-based architectures, however, TasNet and Conv-TasNet remain commonly cited benchmarks.

Wrap-Up

We’ve examined several solutions to the cocktail party problem and seen how latency varies across them — but all in a fairly abstract setting. We’ve scoped the problem statement to just mono signal on voices (really only 2-3 at a time). That begs the question of how these models might behave in the real world, in hearing aids. Some questions that might come to mind include:

- How do we lower the computation required, so these models can operate in hearing aids? Or alternatively, how do we increase the computation capabilities in chips to fit in assistive listening devices?

- What happens if we introduce more background noise?

- Are there hardware designs that might allow us to take in more information besides just a single time series? Could we gather visual cues, for example?

- How do we better handle when there are possibly many more than 2-3 speakers at a time?

- What’s the best way to modify the mixture signal given the separated speaker signals? Should we simply magnify the loudest 1-2 speakers, or is there a smarter algorithm to use?

- What other training or architecture modifications would better suit these models for assistive listening devices?

Follow-Up Resources

- WHAMR!: this paper introduces a dataset that adds reverberation to its audio samples, which better simulates real-life scenarios

- Looking to Listen at the Cocktail Party: Google Research published a speech separation solution that incorporates visual signal

- Disability Project Podcast (on assistive technology): though not about assistive listening devices specifically, this episode provides more visibility into what makes assistive technology suit its users

Special thanks to Adi Ganesh and John McIntosh for talking through the ideas with me.

Update on 2024-07-23: the SI-SNRi equation was corrected to have the correct sign.

In the literature, the term “causal” is used for techniques that don’t use future information and are thus suitable for real-time purposes. However, “real-time” still means processing small batches of data, so I prefer to talk about how large these batches are, or how much lag for which we need to wait.

For this discussion, we’ll focus on the magnitudes of the STFT output and ignore the phases. Although it’s not optimal, when we apply the inverse transform to the speaker TF representations $\mathcal{S}_i(f,t)$, we can assume we use the same phases as the mixture’s TF representation.

Modified audio clips courtesy of online tools for volume, mixing, and conversion.

The authors claim that the 100 frames are close to “one word in speech”, which is shorter than 824ms, so perhaps their setup should be interpreted differently. ↩︎

They’re not quite basis signals because they’re not restricted to be orthogonal to each other.

However, the formally cited definitions of SDRi and SNRi are distinct.